GILBERT "BRONCHO BILLY" ANDERSON

THE WORLD'S FIRST MOVIE STAR

This scary looking hombre is Broncho Billy, and at one time he was the number one movie star in the world. Of course he didn't have much competition because he was the only movie star in the world, a movie star being an actor whose name appears above the title and whose participation in the film is used to market the film.

This scary looking hombre is Broncho Billy, and at one time he was the number one movie star in the world. Of course he didn't have much competition because he was the only movie star in the world, a movie star being an actor whose name appears above the title and whose participation in the film is used to market the film.

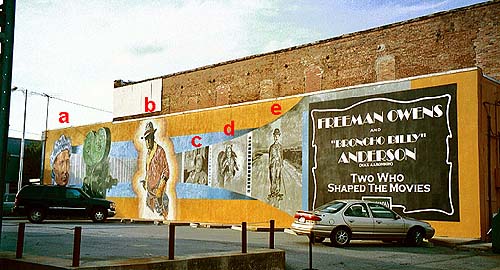

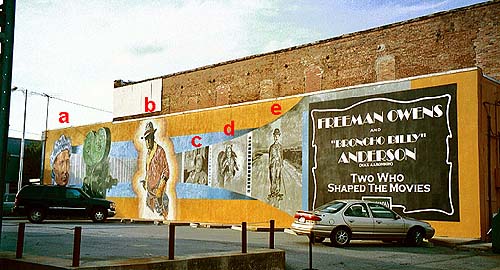

This mural was painted by Michael Wojczuk as part of a program to turn downtown Pine Bluff into a giant art gallery depicting the history and culture of Pine Bluff and the surrounding area. Twenty-two murals were planned. Twelve have been completed. Stop by the Dexter Harding House just a stone's throw from the court house to pick up your Downtown Mural brochure and map. The Broncho Billy mural is on the east side of Main between 2nd and 3rd Streets.

Anderson was born Max Aronson maybe in Pine Bluff, but according to biographer David Kiehn probably in Little Rock. Mr. Kiehn didn't have an actual birth record, but he found two-month-old Max listed as a Little Rock resident in the 1880 census. Anderson claimed both towns as his birthplace at one time or another. There are similar doubts about the date of birth. Sources variously say March 10th or 21st, 1880 or 1882. At about the age of three Max and the family moved from Pine Bluff to St. Louis.

About 1900 he moved back to Pine Bluff to learn from his brother-in-law the ins and outs of buying and selling cotton. He didn't like it much and he tried his hand at theatre and vaudeville. According to the Maskell correspondence referenced below, Max's creative efforts were not well-recieved by either critics or audiences, but after a little stage experience in Little Rock and St. Louis, he headed for New York.

So while growing hungry in New York, he took the suggestion from a theatrical agent that he "pose for moving pictures." He went down to the Edison company and got hired to pose for one reelers. They didn't call it acting in movies then. They called it posing. Acting happened on a stage and involved spoken dialogue. Posing happened in front of a camera and involved goofing around. Movies were not story telling devices in those days. A movie was fifty feet long or so (that's how they sold them, by the foot), and one might just be four minutes of people walking into a store and buying fruit. Or it could be four minutes of a dancer or a juggler or traffic at an intersection.

Then one day Max, who had by then assumed the professional name Gilbert Anderson, had a bright idea. He told his boss that if people could sit still for fifty feet of film, they could be made to sit still for a thousand. How do we do that? says the boss. Gilbert suggests stringing together a thin story and padding it out with "lots of riding and shooting and plenty of excitement," thus creating the immutable paradigm of American commercial cinema. He confessed on behalf of a colleague to stealing the title "The Great Train Robbery" from a popular stage play of the day.

The "facts" contained in the previous paragraph come from a late-in-life interview. So although he claimed to have practically invented the narrative movie, everybody else who might want to share the credit was dead. When auditioning for the job he also claimed that he could ride and shoot, but while filming the first scene he mounted his horse from the wrong side. The horse spooked and threw him. He was relieved of his ridin' and shootin' duties and given several smaller roles. So he couldn't act, he couldn't ride, he couldn't shoot and he warn't special handsom, neither. The fact that he became a cowboy movie star is one of life's little ironies.

He embraced this new art form partly because the stage was hostile to him. Posing for moving pictures was beneath the dignity and pay scale of successful stage actors, so there was less competition for screen work. The medium was new. Artistic conventions had yet to be established, so no matter what you did, nobody could tell you it was wrong.

Mostly there was something about him that captured a viewer's attention. There's footage in the AETN documentary listed in the footnotes demonstrating that in any crowd scene he's the guy you're looking at. He's a big, imposing guy. He has a big moon of a face. The whites of his eyes are very white, and they're outlined by the folds of his cheeks, making them look even bigger. His movements are deliberate and economical. If another actor is dancing a jig in the foreground, you're looking at Our Hero in the background. Star Quality. Same now as then. Everybody can recognize it, but nobody can duplicate it, and no amount of talent can compensate for its absence.

Moving right along, he and old buddy George Spoor formed the Essanay Studio (S & A = "Essanay" Get it?) in Chicago, and they started cranking them out like sausages. They'd shoot between two and five pictures a week, often with no more script than what Max had jotted on the cuff of his shirt sleeve. Max was mostly a producer/director/studio head until one day when an actor refused to do a stunt. He fired the actor, and in the interest of saving a buck, took the role himself. Max appropriated the name "Broncho Billy" from a popular series of stories by Peter Kyne. Trademark infringement, but what the heck. A legend was born.

From 1908 to 1915 Essanay in Chicago and in Niles, CA, cranked out 375 westerns (Again, sources differ. Some say as many as 700), most of them featuring Broncho Billy. So it looks like Max also invented the sequel in a big way. Can you imagine "Rocky CCXIV?"

Essenay was more than a nitrate mill. Charlie Chaplin developed his Little Tramp character there. Max had offered him a meaty deal when his contract with a competitor was up. Unfortunately, he made the deal without consulting his partners. This kind of behavior contributed to the breakup of Essanay. Spoor bought him out and shut the company down. Part of the deal was that Max was to not appear in movies for two years.

Well, after 375 Broncho Billy episodes he'd probably about covered the material anyway, and two years after Essanay closed, the Great War was raging. Audiences were distracted. Tastes had changed. He made a few more westerns, but his bell had rung. He bought himself a theatre and became an exhibitor. He maintained an extravagant lifestyle, frittering away his fortune by 1925. He managed a hotel in San Francisco for a while. He soon dropped out of sight in plain view, settling in a small house in Los Angeles.

When he showed up at the Oscars in 1958 to accept a special Academy award for his early work in silent films, everybody was surprised to discover he was still alive.

He left the world the way he entered it. That is to say, people disagree as to where it happened. He died either in South Pasadena or Woodland Hills, CA. on January 20th, 1971.

Here's the whole mural. Broncho Billy is labelled with a "b." "a" is Freeman Owens, a Pine Bluff native who developed a method of recording sound directly onto photographic film. "c" is Wallace Beery. He has nothing to do with Arkansas. He was just a pal of Owens. "d" is Peggy Shannon, a girl who grew up in Pine Bluff and made a few movies in Los Angeles. "e" is Charlie Chaplin. He also has nothing to do with Pine Bluff or Arkansas. He's there representing the other artists of Essanay Studios.

RTJ--3/1/2002

I got some notes and corrections from Davie Kiehn.

Regarding Broncho Billy's lost years:

"Anderson was a very private person and didn't talk much about his personal

affairs, but being a recognizable figure there is some information about the

"lost" years. In his retirement he had money, at least for awhile, to live

the way he wanted, and whatever he did in the later twenties was probably

not very newsworthy, I suspect, just enjoying life. He did sue his old

partner George Spoor to collect on the proceeds of Chaplin's films, but only

collected $4000 in 1925. Anderson was also sued several times by various

people and in one case, also in 1925, Anderson claimed he was broke and

couldn't pay after he lost in court, another reasonto keep a low profile."

"In the 1930s Anderson was living in San Francisco and managing an apartment hotel on O'Farrell Street. In 1941 he moved to Los Angeles. In 1950 he and

his daughter Maxine tries to get a Broncho Billy series together for

television, but nothing came of it. In his later years he was living on

Social Security and some money from Maxine, who ran her own successful

casting agency."

Regarding the confusion over the location of his death:

"The confusion about his death location is because of where he'd been

staying, the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills. In 1970 he was

moved to their convelescent home in South Pasadena because of his worsening

condition, an invalid near death, and that's where he died. It's listed on

his death certificate, which I've seen. That document didn't provide his

correct birth year, though, it was listed as 1884, thereby further confusing

the issue. Nor was his parents listed; those spaces where marked "unknown."

The information was provided by his daughter Maxine. Obviously she didn't know

him that well."

Regarding the origin of the character name "Broncho Billy:"

"Yes, stories by Peter B. Kyne would be the correct line, although it wasn't

true. Anderson made Broncho Billy's Redemption in 1910 before Kyne wrote any

western stories, and the story Anderson claimed he stole it from, Broncho

Billy and the Baby, was never written by Kyne, but was produced by Anderson

in Niles in 1915. So there's a lot of confusion about the name's origin."

"I think Anderson forgot where the name came from and made this version up;

the information definitely came from him. Kyne was a San Francisco writer

(I've seen his papers, which exist in part at the Bancroft Library here in

Berkeley) and Kyne never commented on Broncho Billy or Anderson.There was a

real life Broncho Billy outlaw in Colorado in the late 1800s, but the name

could have just as easily been fashioned in other ways."

RTJ--3/4/2002

Sources:

Pine Bluff Convention and Visitors Bureau and Pine Bluff Downtown Development, Inc., Pine Bluff Downtown Murals.

Maskell, R. R., correspondence and untitled article on file at the Arkansas History Commission, personal file--Aronson, Max; 1972.

Arkansas Gazette; First Western Movie Star Dies at 90 -- Native of LR; 21 Jan 1971, sec. A, col. 4.

Kiehn, David; personal correspondence. His book, "Broncho Billy and the Essanay Film Company" will be published in 2002.

Arkansas Educational Television Network, Broncho Billy: The First Reel Screen Cowboy, 1998.

Link to: Diane MacIntyre article from "The Silents Majority," 1997.

Link to: Broncho Billy Online Filmography

Link to: Broncho Billy Official Film Festival Web Site maintained by the Essanay Preservation Committee

Arkansas Travelogue home page

This scary looking hombre is Broncho Billy, and at one time he was the number one movie star in the world. Of course he didn't have much competition because he was the only movie star in the world, a movie star being an actor whose name appears above the title and whose participation in the film is used to market the film.

This scary looking hombre is Broncho Billy, and at one time he was the number one movie star in the world. Of course he didn't have much competition because he was the only movie star in the world, a movie star being an actor whose name appears above the title and whose participation in the film is used to market the film.