A hundred yards or so off in the woods on the north side of highway 71 east of De Queen can be found this giant cement head poking out of the ground. You might glimpse it from the road, but there's a path right up to it starting at the parking lot of the East Side Flea Market.

Mabry built his Big Head in 1959 for no external reason I could find. He denied that he did it for the technical challenge. He denied that there was any influence from native American tribes or Easter Islanders. The only explanation he offered that I found was that he wanted "to convey a feeling of massiveness by use of planes and angles." That's all well and good, but the fact that it's SOLID REINFORCED CONCRETE also contributes to the impression of massiveness. The piece is touted as being over seventeen feet long, but the aboveground portion measures sixteen feet, six inches.

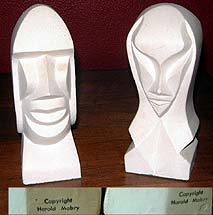

The literature found on this work most often calls it "Easter Island Head," but Harold referred to it in print as "Big Head" or "Male Head," because a second (female) head was planned, to be set at right angles to this one. His son Steve told me over the phone that several miniature prototypes of the  pair of heads were produced; and that if viewed together it's really obvious that they weren't inspired by the heads on Easter Island. He described the female as resembling the classic gray space alien of modern folklore, somewhat ahead of its time in 1959. Here's a picture Steve e-mailed me of a pair of 7-inch models. The original prototypes were two feet tall.

pair of heads were produced; and that if viewed together it's really obvious that they weren't inspired by the heads on Easter Island. He described the female as resembling the classic gray space alien of modern folklore, somewhat ahead of its time in 1959. Here's a picture Steve e-mailed me of a pair of 7-inch models. The original prototypes were two feet tall.

A mold was excavated in the native red clay on site. The surface of the mold was detailed and smoothed with plaster, the back and sides were buttressed with lumber; and local contractor John Jacobs poured the statue face down with a hinge built into the base. Jacobs poured a foundation slab at the same time. A truck chassis and other steel items were used to reinforce the concrete. Two months later (in mid September of 1959) a bulldozer and dragline arranged by Judge Tom Coulter tipped the head upright and Harold dabbed it with paint to simulate natural stone. Shortly thereafter carloads of passersby began pulling off the road to visit and photograph the site.

Forgive my Monday morning quarterbacking, but once I had gone to that much trouble to make a mold, I think I might knock out a dozen or so fiberglass copies before filling the trench with cement. The fiberglass copies could be sold, moved, rearranged, easily carried by four guys, maybe even stacked like dixie cups. Of course, in Arkansas the whole world is a target, and within a couple of weeks those fiberglass statues would be shot full of holes just like the roadsigns. I guess there was a certain wisdom in Harold's choice of medium.

Mabry intended to build a workshop near the head, but changed his mind, thinking that traffic would assume the head was an advertisement for a professional shop and not a work of art for its own sake. He found another site for his workshop, and a few months later he started building the new Hurrah City near the Big Head.

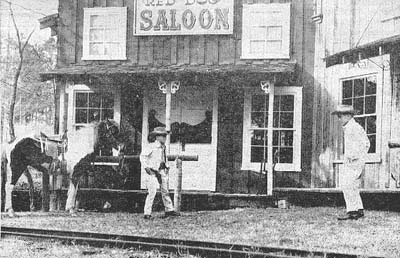

Here's a picture of Mabry's attraction from the Hurrah City Chronicle, published as a promotion (c. 1960) and reproduced here courtesy of the Mabry estate. As you can see, it's a miniature western town, scaled for preadolescents. The two youngsters in the photo are staging a classic western showdown in the street, perhaps a conflict over the fact that they both showed up wearing the same outfit.

Here's a picture of Mabry's attraction from the Hurrah City Chronicle, published as a promotion (c. 1960) and reproduced here courtesy of the Mabry estate. As you can see, it's a miniature western town, scaled for preadolescents. The two youngsters in the photo are staging a classic western showdown in the street, perhaps a conflict over the fact that they both showed up wearing the same outfit.

Hurrah City was comprised of a few buildings, the Red Dog Saloon, a railroad depot and mercantile store, a miniature railroad called the Pepper Creek and Northern, a pond and a log house museum. The miniature railroad boasted a mile of track and two locomotives, one diesel power plant for everyday and one 1/4 scale coal-fired steam 4-4-0 American type for special occasions. A ride on the PC&N lasted fifteen minutes. When the attraction closed, all assets were sold off except the Big Head, which was too massive to move. It's cheaper to build a new one on the other side of the Atlantic than to move this one to the other side of the street.

Note: Promotional literature for Hurrah City claims that the log house museum contained a dinosaur skull and dinosaur footprints found in the rocky bottom of Pepper Creek. If those specimens are what Harold thought they were, and if they can be tracked down, they would be valuable to people studying the Lockesburg fossils and the Nashville trackways, both found nearby. If you know where those specimens are, contact me at Travelogue.

Hurrah City took its name from the tent city that eventually became De Queen. Here's how that happened. A railroad man with the Kansas City Southern Railway was building a line from Kansas City to Baton Rouge and he ran out of money here. These railroad workers lived seminomadic lives in tent cities, and there were three such tent cities here in the neighborhood when the work ran out. The names of the tent cities were Calamity, Accident and Hurrah City.

The railroad rep tried to put together the funding to finish the last leg of his railroad; and as part of a deal with a Dutch tobacco merchant named John A. DeGeoijen, he promised to name a town after him. Hurrah City was chosen as the location because it had five log buildings, including a Hotel. Something like a hotel, anyway. It was a 12-x-18 log house, a private residence. The lady of the house often took pity on the railroad workers, fed them and let them sleep on the floor. The Mister objected to that and began charging rent. A sign was hung outside the "Hotel de Horse" promising "food for man and beast." Such was the state of civilization in southwest Arkansas in 1897. I have yet to find a historical origin for the name Hurrah City or Hotel De Horse.

"De Queen," on the other hand, is what happened to "DeGeoijen" when the Anglos who typed up train schedules tried to make sense out of this Dutch name. After all, the conductors had to shout out, "Next stop: DeGeoijen." The pronunciation was phoneticized DeWheen and DeHOOyen and probably some others. De Queen (two words, and often pronounced "DEE-queen") was finally settled on. I didn't read any reference as to how DeGeoijen felt about the change, since the namesake town was supposed to be part of the deal.

Harold Mabry made his living as a sign painter. He had minimal formal art training consisting of a few classes at the local junior college. He illustrated several calendars and made prints of watercolors on local subjects as promotional giveaways for the Horatio State Bank a few miles south of De Queen. Some of those prints can still be had from the bank these many years after Harold's passing. (d. 8 April 1992) While researching this story I visited the Horatio State Bank and they gave me three limited edition Mabry prints, signed and numbered by the artist.

Everybody I spoke to in De Queen agreed that Harold was an eccentric genius, but when I asked for individual instances of eccentric behavior or evidence of genius his neighbors gave me nothing specific. I saw talent, but not genius; and to be called eccentric in Arkansas could mean just about anything. Billy Ray McKelvy, editor of the De Queen Bee Daily Citizen told me that Harold's opening comment to him at their first meeting was, "I ain't no damn genius." I asked Steve about this and he said that his dad wasn't at all eccentric. He just didn't care that much whether or not people understood what he did, so he never seriously explained himself to his neighbors. Ten people asking why he made The Big Giant Head would probably get ten different answers.

Why did he actually do it? Because it was neat. What more reason did he need?

RTJ--11/1/2001

Sources:

Hoofman, Judy; De Queen Centennial History 1897-1997, A Photographic History of the City of De Queeen, Arkansas; Looking Glass Media, 1997.

Mabry, Harold; Hurrah City Chronicle, vol. 1, no. 1. (promotional newspaper of the 1960's tourist attraction.)

Mabry, Harold; Profiles of the Past, pub. De Queen Bee Co., De Queen, AR. p. 14.

Stone and Steel, A Sculptural Tour of Arkansas, pamphlet published by Arkansas Historic Preservation Program.

Motorists Along Highway 70-71 Encounter Real Traffic Stopper, De Queen Bee, 1 October 1959; page 1.

Interviews and Correspondence: Steve Mabry, (son of Harold). Billy Ray McKelvy (Editor: De Queen Bee Daily Citizen).

Special Thanks to the Sevier County Museum staff.