THE BOWIE KNIFE AND THE ARKANSAS TOOTHPICK

Pictured at right is a reconstruction of James Black's  blacksmith shop in Old Washington State Park. It's not accurate in every historical detail, but it is authentic, typical of an 1830's blacksmith shop in this part of the frontier; and it is built on the exact spot where James Black's shop stood when Jim Bowie walked in the door and handed him a whittled wooden model of the knife he wanted Black to craft.

blacksmith shop in Old Washington State Park. It's not accurate in every historical detail, but it is authentic, typical of an 1830's blacksmith shop in this part of the frontier; and it is built on the exact spot where James Black's shop stood when Jim Bowie walked in the door and handed him a whittled wooden model of the knife he wanted Black to craft.

Four weeks later, in January of 1831, Black had made the knife for Bowie and he had also made a second knife, a modification of Bowie's design. He said that he had always believed that a knife should be made "for peculiar purposes," whatever that meant. He told Bowie to pay the agreed price and take the knife he preferred. Bowie chose Black's design, which was like his own, but was double-edged along the length of the curve from the point. In other words, the top of the blade is sharpened toward the tip. That must have been the innovation that appealed to Bowie, for he could still use most of the thickness of the back of the blade to parry and have an additional sharpened edge for back slashing.

Immediately thereafter, on Bowie's return trip to Texas (he had just become a citizen of Texas, which was then Mexico), he was attacked by three men who had been hired to kill him. He killed all three with his new knife. This encounter brought immediate fame to the Bowie Knife and to James Black. From then on, any traveler passing down the Chihuahua Trail would stop at Black's shop and ask for a knife "Like Bowie's." Eventually this was shortened to Bowie (say "BOO-ee") Knife.

After the battle of the Alamo five years later, the knife accompanied its owner into the realm of legend. If it was recovered at all, it was probably appropriated by a nameless Mexican soldier as a war trophy. Because the Knife disappeared, though, modern knifemakers indulge in a certain amount of interpretation concerning what exactly is a Bowie Knife. Bowie was after all a frontiersman and famous knife fighter long before 1831 and doubtless owned many knives in his career. Black's design can be construed as the final step in the evolution of Mr. Bowie's ideal knife. Any of the knives in that evolutionary chain could be called a Bowie Knife, and the design continued to evolve after Bowie's death.

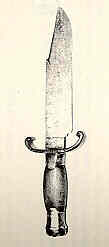

The knife pictured at left bears James Black's mark on the blade and was made and sold as a Bowie Knife. Black quit making knives in 1839, so it seems likely that this design is pretty close to that of Jim Bowie's personal knife. (note: this picture comes from Mandy Medearis' book, Washington, Arkansas: History on the Southwest Trail.)

The knife pictured at left bears James Black's mark on the blade and was made and sold as a Bowie Knife. Black quit making knives in 1839, so it seems likely that this design is pretty close to that of Jim Bowie's personal knife. (note: this picture comes from Mandy Medearis' book, Washington, Arkansas: History on the Southwest Trail.)

Black's skill was without peer. Governor Jones wrote, "I am certain that Black possessed the Damascus secret.... He often told me that no one taught him his method of tempering steel, but that it came to him in a mysterious manner which he could not explain." This secret he kept to himself. He tempered his blades behind a leather curtain, shielded from the curious eyes of onlookers and even those of his own partners.

On his seventieth birthday (in 1870) he decided to pass on his steel-tempering secret to the family that had cared for him throughout his infirmity and old age. But he hadn't been a practicing blacksmith since 1839 and he had forgotten all his secrets. The only thing he remembered was that there were ten separate steps.

YET ANOTHER BIZARRE ARKANSAS BIOGRAPHY

Black's biography reads like a Dickens novel. Born 1 May, 1800 in Hackensack, New Jersey, he ran away from home at the age of eight because he didn't get along with his stepmother. He ended up in Philadelphia. He wouldn't tell authorities any information about himself, lest they send him back to his unhappy home. They judged him by his build to be eleven years old and they apprenticed him to a silversmith. When he reached the official age of 21 (the actual age of 18) he was released from his indenture and he joined the westward migration into the new territories.

He held a number of jobs along the way, ferryman, deckhand on a steamer, all adventurous stuff. Then one day he met Elijah Stuart, they became friends and decided to make a go of it in the new territories. The two of them made their way to this place, which was then fourteen miles from Mexico. Stuart built a tavern and Black took a position with a blacksmith named Shaw. His thirteen years as a silversmith in Philadelphia came in handy. While the Shaws handled the coarse work like horse shoes and wagon wheels, Black worked exclusively on guns and knives.

Parenthetical note: It was at Elijah Stuart's tavern that a group of gentlemen including Crockett, Bowie and Travis plotted to take Texas from Mexico.

Things were just peachy for James Black for the longest time. Black was even made a partner in the business. Eventually, though, Black fell in love with the boss' daughter, Anne. Shaw, for some yet unknown reason, was violently opposed to any match and forbade the marriage. Black reasoned that he could win Shaw's approval if he were his own man, so he made a settlement with Shaw, accepting a note in lieu of cash for his share of the partnership. He borrowed against that note to build a cabin, a smithy, dam and a mill at the Rolling Fork of the Cossatot. The company grew and prospered.

Then one day the sheriff came and threw them off the land, declaring it to be Indian land and that Black's new company had no right to be on it. Also turns out the note given to Black by Shaw wasn't worth squat. It was a dissolution of partnership without regard to financial settlement. He had been screwed.

Black got even by marrying Anne. Shaw just got angrier and angrier.

Black set up his own smithy and as trade grew and orders piled up he took Shaw's son, his brother-in-law, into his business. Old Shaw must have thought his family was being dismantled and stripped from him. Black never shared his secrets with young Shaw, probably to insure that old Shaw never got his hands on them.

Anne and James had three boys and a girl before Anne died in 1838, and her death didn't improve Black's relationship with old Shaw. In the summer of 1839 Black fell ill, and while he lay helpless in bed, old Shaw crept into the house and attacked him with a club. The family dog attacked old Shaw and drove him away, saving Black's life, but the clubbing had damaged Black's eyes.

Black headed back to Philadelphia to consult with learned physicians about his eyesight. He was diverted to Cincinnati, where an unprincipled medical quack took his money and left his eyesight further damaged. Black continued on to Philadelphia, where legitimate physicians were unable to help him.

He returned home to discover that old Shaw had sold all his (Black's) property and skipped town with the cash.

For two years, Black lived with the Buzzard brothers on their plantation until a man named Isaac Newton Jones, a surgeon from Bowie(!) County Texas adopted him into his own family. Black lived with the Jones family for thirty years. His children were adopted into other pioneer families. It was to young Daniel Webster Jones, son of Isaac, that Black tried and failed to present his metallurgical secrets in 1870.

Incidentally, that kid became Governor of Arkansas in 1890 and served for two terms.

THE ARKANSAS TOOTHPICK

Pictured here is one of the master knifesmiths at Lile's Handmade Knives in Russellville. In his right hand is a Bowie and in his left is an Arkansas Toothpick.

Pictured here is one of the master knifesmiths at Lile's Handmade Knives in Russellville. In his right hand is a Bowie and in his left is an Arkansas Toothpick.

James Black is often credited with the invention of the Arkansas Toothpick, although this connection is somewhat weaker and is possibly due to confusion between the Arkansas Toothpick and the Bowie Knife. Arkansas Toothpicks and Bowie Knives manufactured in England were both sold as Bowie Knives. Still, Black was renowned for making throwing knives and if he did not invent the Arkansas Toothpick, he certainly contributed to its development and doubtless manufactured hundreds of them.

The Arkansas Toothpick is essentially a long, heavy, balanced dagger, slung in a holster across the back, drawn over the shoulder and flung optimistically at a distant enemy. When I say long, I mean a blade of fifteen to twenty-three inches. The Bowie Knife was also enormous. It was said that a Bowie had to be sharp enough to use as a razor, heavy enough to use as a hatchet, long enough to use as a sword and broad enough to use as a paddle.

OLD WASHINGTON HISTORIC STATE PARK

The plan hatched in 1958 by James Pilkington and Talbot Feild is to turn the whole town of Washington into a historical preserve something akin to Colonial Williamsburg. As property becomes available, it is purchased for the park. As money becomes available historic buildings are restored. So far there are over 40 restored sites, buildings, points of interest and museums that can be visited. Here you'll find one of the best gun collections in the country, a print shop with antique presses, a black history museum, the Confederate State Capitol building, Elijah Stuart's Tavern and much more.

They offer guided tours, interpretive services (that means they'll tell you the histories of all the buildings) and the park hosts occasional events like mountain man rendesvous and Civil War reenactments. Find Old Washington twelve miles north of Hope on highway 4.

RTJ--8/1/98

UPDATE

On Saturday (4 Nov 06) I attended a reenactment weekend at Old Washington State Park where I spoke with their resident knifesmith at the blacksmith shop. I don't know if he came up with this theory himself or if it is something that is going around knifesmith circles, but he told me that he believes the classic design of bowie knife is Bowie's own design and not that of James Black.

At first I thought this was just one of those notions that crops up from time to time only later to be forgotten, but as I was driving home I realized that even if you delete all the parts of his theory that are speculative, he still has a pretty good case. Here goes:

There's a knife known to have come from Black's shop that has the words "Bowie no. 1" engraved on it. It's got a long, heavy blade and a sharpened clip, but unlike the classic bowie, it has an offset coffin handle with silver rivets. Black made lots of knives over the years with offset coffin handles and silver rivets. That was his typical style. What are the chances that Bowie's design would reflect Black's typical style AND that Black's modified design would be done in an atypical style?

Second point. Two classic bowies have turned up which very likely came from Black's shop -- one from the site of the Mexican camp near the Alamo, the other in a California collection. A third knife matching the description of the large coffin handled design was described in the posession of a Mexican who accompanied the Zebulon Pike expedition. That Mexican was a veteran of the battle of the Alamo.

This knifesmith concluded that Bowie had bought BOTH designs from Black and that in telling the story Black mentioned (without lying, exactly) only that Bowie had bought his design, allowing potential customers and later historians to conclude that the Black design was the classic Bowie. The only one who might authoritatively contradict him had been killed at the Alamo.

Those are the essential elements of the argument. I haven't gone to any trouble to check this story out, but if the facts presented in the previous three paragraphs are accurate, I'd have to agree with the knifesmith, that the classic bowie probably is Bowie's own design.

The proof of the theory hinges on that Mexican veteran's knife and how well it can be linked to Bowie and the Alamo. That's the difference between proven and not proven. Don't forget that Black made thousands of knives in his career and they circulated all over the southwest. Also, people copied his designs and forged his maker's mark. The evidence is tantalizing, but still circumstantial.

RTJ--11/5/2006

Arkansas Travelogue home page

SOURCES

"Billy," Old Washington Historic State Park interpretive services.

Chadwick, Susan. Bowie Knife, The, Texas Monthly WWW Ranch. 1998.

Medearis, Mary. Washigton, Arkansas: History on the Southwest Trail. (c)1976 by the author. Etter Printing Company, Hope, AR 71801.

Thorp, Raymond W. Bowie Knife. University of New Mexico Press, 1948.

blacksmith shop in Old Washington State Park. It's not accurate in every historical detail, but it is authentic, typical of an 1830's blacksmith shop in this part of the frontier; and it is built on the exact spot where James Black's shop stood when Jim Bowie walked in the door and handed him a whittled wooden model of the knife he wanted Black to craft.

blacksmith shop in Old Washington State Park. It's not accurate in every historical detail, but it is authentic, typical of an 1830's blacksmith shop in this part of the frontier; and it is built on the exact spot where James Black's shop stood when Jim Bowie walked in the door and handed him a whittled wooden model of the knife he wanted Black to craft. The knife pictured at left bears James Black's mark on the blade and was made and sold as a Bowie Knife. Black quit making knives in 1839, so it seems likely that this design is pretty close to that of Jim Bowie's personal knife. (note: this picture comes from Mandy Medearis' book, Washington, Arkansas: History on the Southwest Trail.)

The knife pictured at left bears James Black's mark on the blade and was made and sold as a Bowie Knife. Black quit making knives in 1839, so it seems likely that this design is pretty close to that of Jim Bowie's personal knife. (note: this picture comes from Mandy Medearis' book, Washington, Arkansas: History on the Southwest Trail.) Pictured here is one of the master knifesmiths at

Pictured here is one of the master knifesmiths at